Reading has become increasingly difficult for me since becoming a father. Gone are the days (for now) when I could literarily lose my self in a book, sailing the Black Sea as an argonaut with Jason; investing the profits of my smash-hit plays in ill-fated brick and mortar broadway ventures alongside Neil Simon in the 1960s. Different times, parallel characters. Now, the act of opening a book is a provocation that requires immediate satisfaction from one of my children, like the slap of a glove across the cheeks. They crawl over the book, seize it, or create a catastrophic diversion.

It's not to say I can never read, but I have to take my chances. Early mornings after chores but before they're up. At night after they're in bed (a recipe for falling asleep and dropping book on face). There's little method in my limited reading these days. But there is a regular practice of sorts that keeps me chugging along. I'm reading thematically. Different books, different genres. The same time and place from different perspectives. And it all starts with three books on China.

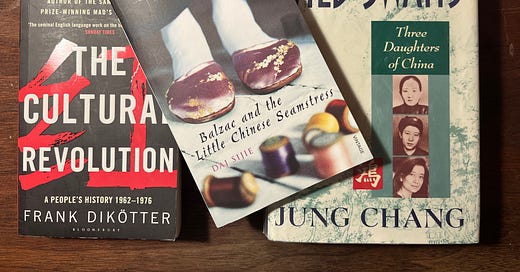

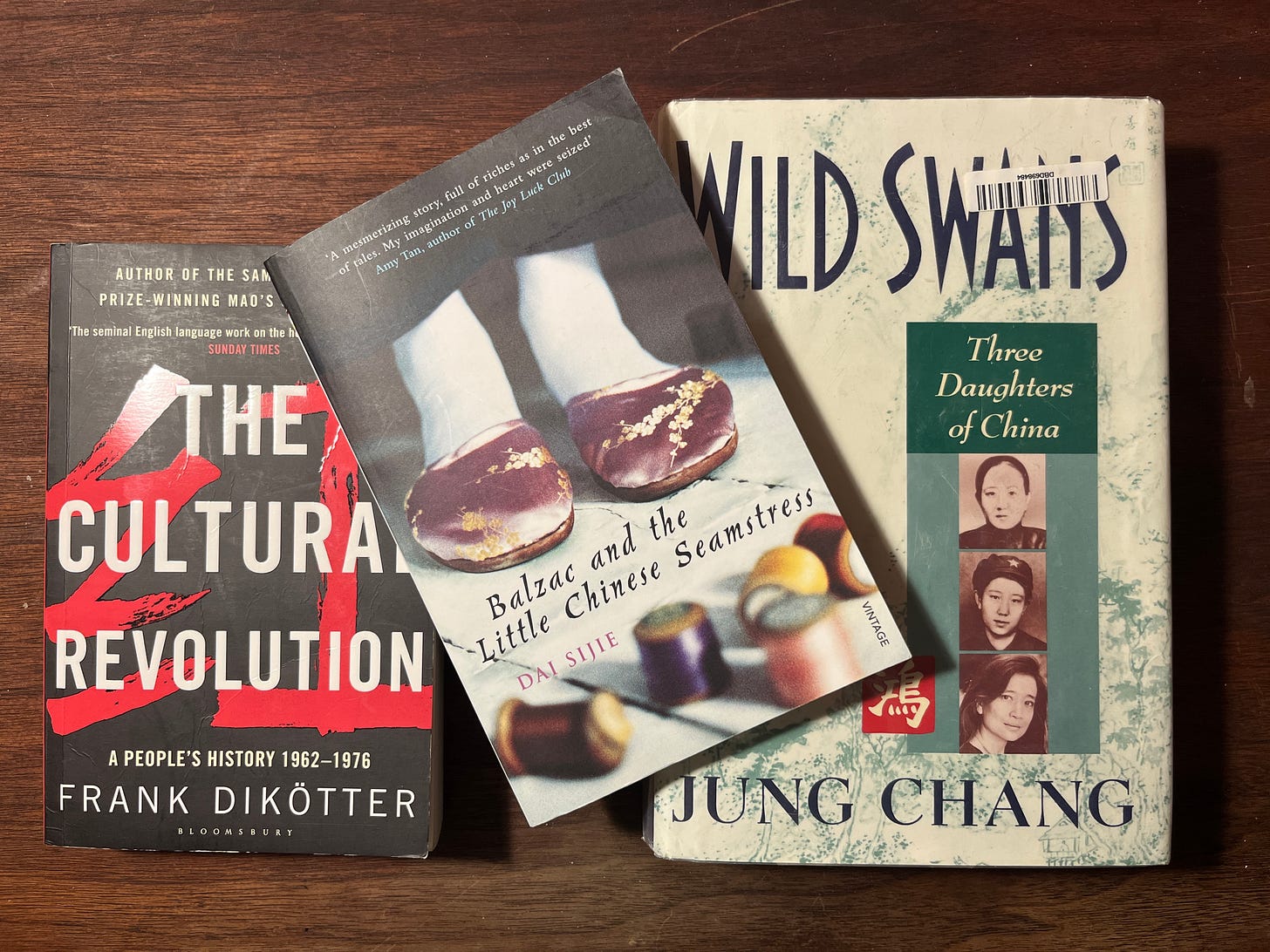

A history, a biography and a novel.

I didn't plan to do this, it just kind of happened. For some reason I wanted to know about the cultural revolution. Maybe it's because it gets referenced a lot. Usually as a pricking pin to deflate someone's idea to change something for the better at scale. I wanted to see what it was like for people when someone as remarkable as Mao managed to practice what he preached.

Each book made an impression, but it was how they all added together, and enriched each other that got me thinking this is a really lovely way to read.

The Cultural Revolution: A People's History 1962-1976 by Frank Dikötter.

This short history responds to my initial question: what on earth was the cultural revolution? How did it come about? When? And so on…

The clearest memory I have of this are the 1960s tweets. Denunciations. Often by students against professors. Handwritten on single sheets and pasted to walls of universities. Naming, shaming, calling out, threatening. Violent words that often lead to violent and humiliating consequences for the denounced.

Wild Swans by Jung Chung

The multigenerational biography adds character to Dikötter's general history through the lives of three generations of women who embody the before, during and aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. Written by the granddaughter, and recounting and reflecting on the experiences of her mother and grandmother. Most poignant to me is the faith and active participation of the author's mother in the cultural revolution. A party woman through and through, she is both lifted up, and severely put down by the revolution. She rises through the ranks to positions of high local leadership. Her alliances get her promoted, then cancelled, and incarcerated in re-education camps. She never seems to lose her faith in the party, the people or the system. The only moment she contradicts them is when (why do I remember this?) the birth of one of her children leaves a piece of placenta inside her and she insists on an operation that will save her life.

Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress

Two young men from the city are sent to the countryside. Virtual prisoners I suppose, but I don't think it's a re-education camp as such. It’s part of a policy designed to bring city kids into contact with the purported virtues of the rural poor. They certainly learn how to live like poor people. The scene that sticks with me is an occasion when they're invited to dinner by a man with no food. He prepares 'stone soup'. Mildly flavoured warm water, served in a bowl with pebbles in it. You use chopsticks to put the pebbles in your mouth, and suck them to make the most of the flavour, and give your body the sense of eating food.

I think I could make this into a very popular restaurant concept.

Come to my Michelin starred Stone Soup. Choose your delicious broth, and stones (stainless steel at the lower end, to ceramic, jade or pearls).

I'm going to make a fortune.

Share this post